Off To Tybee for a family week - our 38th. No memos until after we return around the 20th. Have a great and safe week.

===

Bring it on.

Every nation that has tried Socialism has proven it fails and enslaves. Read Hayek's "Road To Serfdom" if you believe otherwise.

So if that is what the Demwits want then nominate Bernie and let them try it.

If Americans are stupid, as Gruber says we are, then we too deserve what we get. (See 1 below.)

===

Like Rodney Dangerfield, Iran gets no respect. Obama and Kerry have given them everything else they wanted why are they holding back? (See 2 below.)

===

Greece is one thing, China is another.

Stock losses on the part of Chinese investors cannot be avoided even if the government rushes in to stabilize the market. The Chinese Government might postpone the inevitable but nature has a way of even bringing Socialism and Communism to their knees. Stay tuned. (See 3 and 3a below.)

===

Today various things happened because of technology failures.

The White House said they were neither connected nor attributed to 'terrorism or whatever euphemism Obama uses. Thus, the meeting here at The Plantation Club, on July 14 at 5 PM, on cyberspace, should be even more interesting and timely. I urge everyone, who can, to attend.

===

===

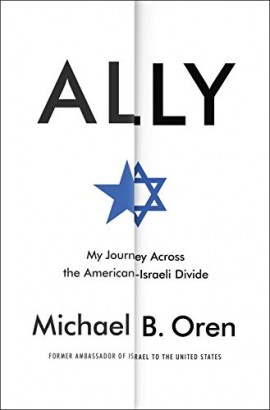

David Lowe, is the brother of one of my dearest Savannah friends and fellow memo reader. David wrote a review of Micjael Oren's book which is well worth reading. (See 4 below.)

And this from David's boss! (See 4a below.)

===

Finally this from a very long time friend, fellow memo reader and Marine. (See 5 below.)

===

Dick

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1)

Wealth Gap

A Commentary By John Stossel

Nearly 10,000 people turned out to hear Bernie Sanders in Wisconsin. Why? Apparently, many Democrats want socialism.

Sanders is the Vermont senator who is running for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination.

Sanders calls himself a "democratic socialist," not to be confused with New York City mayor Bill de Blasio's preferred label, "social democrat," but both believe that more power and wealth in the hands of government (less in the hands of free people and the free market) is a good thing. They just don't want you to think they're dictators like Stalin. They may institute terrible economic policies, but they'll have the backing of voters.

More Democrats say they plan to vote for Hillary Clinton, but she's already sounding more socialist to ward off the Sanders challenge, slamming "corporations making record profits."

In crucial early-voting state New Hampshire, next door to Sanders' home state, Sanders polls at 35 percent to Clinton's 43.

A big reason for Sanders' appeal is his relentless criticism of America's wealth gap. His "solutions" include raising the federal minimum wage to $15, completing the government takeover of healthcare, mandating paid maternity leave, punishing bankers, expanding Social Security and spending more on job training.

We must do these things, he says, because "wealth is centered in the hands of a very few." He accuses Republicans of preferring it that way.

That's a common refrain on the left, and it appeals to many voters. Some poor people think they'll be helped by "redistribution," and rich people who don't understand the process that made them rich want more rules to "level the playing field."

I wish someone would educate them and ask Clinton, "What's wrong with 'record profits'? What do you think happens to that money? Greedy executives just sit on it? No! Profit is reinvested in ways that make all of us better off!"

Libertarians and real free-marketers agree that too few people are rich but understand that today it's largely because of government.

The minimum wage laws that Sanders likes decrease the odds that people on the bottom rung will get hired and learn the basics of being a good employee. Other laws make it harder for them to move up.

Today's thicket of regulations means entrepreneurs must hire lawyers and "fixers" to get anything done, and those middlemen cost money. Not a big problem if you're already rich, but a big obstacle if you're just starting out, or trying to expand a small business.

Requiring paid maternity leave makes companies even more wary of hiring young women. The law forbids such discrimination, of course, but bosses just give some other reason for not choosing female applicants.

That same unintended consequence happened with the Americans with Disabilities Act, the well-intended law supported by Democrats and Republicans meant to help more disabled people enter the workforce. But fewer disabled people work now that the law is in effect. Fifty-one percent held jobs when the law passed; now only 32 percent do.

Greece "protects" workers by banning part-time work and banning working more than five days a week. You'd think American socialists would learn something watching Greece fail. But, no, they never learn.

Government interventions in health care -- such as Obamacare -- haven't made health care cheaper, but they sure helped rich insurance companies. By writing the companies' roles directly into the law, Obamacare makes it harder for others, such as the new fee-for-service health stores, to compete.

Complex financial regulations mean that rich investors who are already cozy with big law firms, big banks and the Fed are better at understanding and manipulating the rules than a small "angel investor" who wants to back a new invention or interesting start-up.

For 200 years, poor Americans pulled themselves out of poverty by finding new and better ways to do things, or just by working hard. Today, fewer lift themselves up. One big reason is that rules meant to help poor people end up favoring the well-connected rich while keeping poor people dependent.

Sen. Sanders and his fellow socialists should stop callously ignoring how government makes life harder for poor people.

John Stossel is author of "No, They Can't! Why Government Fails -- But Individuals Succeed." For other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit www.creators.com.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2) Pro-Iran Group Head Demands R-E-S-P-E-C-T for Iran in Negotiations

A well-known Iranian American advocate is wagging his finger at the United States for failing to show proper respect for and grant equal footing to the Islamic Republic of Iran.

If he weren't someone regularly cited in the mainstream media and appearing regularly on national newscasts, the piece published recently by the president of the National Iranian-American Council, Trita Parsi, could be ignored.

However, Parsi has a PhD from Johns Hopkins' International Studies School. He has appeared on major media outlets such as CNN, the BBC, NPR and Al Jazeera. he has published in the New York Times, the Financial Times, the Los Angeles Times and the Wall Street Journal.

In addition to garnering key air and print time, Parsi's organization boasts some major players on its advisory board. There are several former U.S. Ambassadors (Thomas Pickering and John Limbert) as well as a current member of Congress (Wayne Gilchrist (D-MD) and a former member (Jim Moody (D-WI). As such, his analysis of the ongoing (and going and going) nuclear talks between Iran and the P5 + 1, including the U.S, is worth noting.

In an article he posted on July 2, "Dignity: the Hidden Factor in the Iran Nuclear Talks," Parsi lectures the U.S. and its allies for failing to recognize that dignity - to wit, treating Iran as a full and equal partner, on equal standing and with equal claims to trust - is imperative.

Parsi points out numerous ways in which Iran is not being treated in such a way as to allow it to be at the table and to negotiate with dignity.

While Parsi still thinks the deal between Iran and the P5+1 is going to be consummated while the parties are in Vienna this week, he is clearly sending a signal to somebody or many people, that failing to grant Iran the dignity Parsi believe it is due could have dire consequences.

Parsi bristles at the idea that the nuclear talks are cast by Americans in terms of what Iran "will be 'allowed' to keep in terms of nuclear structure." Uh uh, Parsi wags his finger. How dare the talks be presented in this way, as if Iran can be told what it can and cannot do.

Wait a minute. Isn't that the point of these nuclear talks? The reason these talks are being held is that a nuclear Iran will be a global threat to all living things. They are indeed about Iran negotiating for the right to do certain things in exchange for the major world powers ceasing the punitive measures they have imposed on Iran for doing what it wants without regard for the safety and security of the rest of the world.

But, Parsi says, if there is any suggestion that Iran is unequal to the other parties, that could sound the death knell to the talks and any diplomacy at all. Parsi goes on to explain that the Iranian foreign minister "oftentimes refers to the other countries in the negotiations as his partners, reflecting equality." But that isn't how Iran is treated. How unfair!

Of course the idea that Iran should be subject to inspections by outsiders of its military sites is an outrage, and that's obvious because no other country is burdened with such intrusiveness. Really? What other nations are threatening to exterminate another nation? What other nation has repeatedly barred inspectors from performing their assessments, after agreeing to allow them?

Parsi takes further umbrage at what he says is a change in inspections of nuclear sites as agreed to in Lausanne, Switzerland. On this point Parsi may be right that the U.S. agreed to "managed" inspections, but that is not what the American people or members of Congress are prepared to accept. The "anywhere, anytime" inspections of Iranian sites may not be palatable to the Iranians, but it is hard to imagine that Congress will cave on this even if the administration did.

But Iran's Ayatollah Khamenei told his people in late May that he would absolutely not permit inspections by outsiders of Iranian military sites or interviews with its scientists by westerners.

If the U.S. and other world powers believe there must be access by inspectors to those sites and Iran believes there cannot be access to those sites, it is hard to understand how a deal can be reached, dignity or no dignity.

Parsi gets around this problem by suggesting that Iran would be able to permit such visits, but only if they were not told they had to permit those visits. In other words, don't make it a requirement and then there will be no affront to Iran's dignity. Perhaps, but there will also be no way to enforce anything not stated as a requirement. And therein lies the real problem with Parsi's dignity talk.

Parsi's insistence on dignity is only reasonable when the party demanding dignity has never given others cause to distrust it. And if there were no reason for the western powers to distrust Iran without demanding certain conduct, these talks would not be taking place. But there is and they are. And dignity is hardly the primary stumbling block.

About the Author: Lori Lowenthal Marcus is the US correspondent for The Jewish Press. She is a recovered lawyer who previously practiced First Amendment law and taught in Philadelphia-area graduate and law schools. You can reach her by email: Lori@JewishPressOnline.com

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3)-

China’s Stock Plunge Is Scarier Than Greece

There are four basic signs of a bubble, and the Chinese stock market is on the extreme end of all four.

A stock-market display in Shanghai, China, July 6. PHOTO: PEI XIN/ZUMA PRESS

China’s state-sponsored stock-market rally is unraveling, with potentially dangerous consequences. The first major sign that all wasn’t going according to script came on June 15. Chinese had awakened expecting big gains because it was President Xi Jinping’s birthday, but the Shanghai market fell more than 2%. One deeply indebted day trader committed suicide by jumping out a window, his net worth wiped out by the collapse of a single stock that he had borrowed heavily to purchase. The market has since fallen by another 25%—and some fear that prices could go much lower.

In most countries, no one thinks there is a link between a leader’s birthday and the market. That such a theory prevails in China reflects the widespread belief that Beijing’s authoritarian government can produce any economic outcome it wants. Now trust in China’s ability to command and control the economy is faltering. If trust collapses, the global repercussions could be more severe than those from the Greek debt crisis..

When China’s economy slowed following the 2008 global financial crisis, Beijing pumped massive amounts of liquidity into the system. First that money went into the property market, later into the various debt-related products sold through the shadow banking system. But when property slumped and the shadow banks started to pose systemic risks, China had only one major market left to flood—stocks.

Funneling some of China’s $20 trillion in savings into stocks was a last-ditch effort to revive flagging economic growth by giving the country’s debt-laden companies a new source of financing. The aim was to trigger a slow and steady bull run, but the somnolent stock market exploded into one of the biggest bubbles in history.

There are four basic signs of a bubble: prices disconnected from underlying economic fundamentals, high levels of debt for stock purchases, overtrading by retail investors, and exorbitant valuations. The Chinese stock market is at the extreme end on all four metrics, which is rare.

The sharp equity rally took place despite sputtering economic growth and shrinking profits. By official count, margin debt on the Chinese stock market has tripled since June 2014. As a share of tradable stocks, margin debt is now nearly 9%, the highest in any market in history. At the leading brokerages, 80% of margin finance has been going to retail investors, many of them new and inexperienced.

Today China’s 90 million retail investors outnumber the 88 million members of its Communist Party. Two thirds of new investors lack a high school diploma. In rural villages, farmers have set up mini stock exchanges, and some say they spend more time trading than working in the fields.

The signs of overtrading are hard to exaggerate. The total value of China’s stock market is still less than half that of the U.S. market, but the trading volume on many recent days has exceeded that of the rest of the world’s markets combined. Turnover is 10 times the level seen at the peak of the previous China bubble in 2007, and virtually the entire market inventory is changing hands every month. Such frantic activity has pushed up valuations for companies large and small, with the broad CSI 500 index trading at 50 times last year’s earnings and the Nasdaq-style board Chinext valued at 110 times last year’s earnings.

Since the June 12 peak, nearly $3 trillion in value has been erased, as Beijing takes increasingly desperate measures to arrest the price collapse. The authorities have cut interest rates and transaction fees. They have directed mutual funds and state pension funds to buy stocks. Over the weekend they panicked and reversed course by suspending new initial public offerings, suddenly choking off a source of the new corporate funding they had been trying to create. This comes when the real cost of corporate borrowing is high. Any further reduction in interest rates could accelerate the outflow of capital, after a record $300 billion has already left China this year.

The continuing crisis is viewed, locally and globally, as a test of China’s control over the economy. The “Beijing put”—a perception that Chinese economy and markets are backstopped by the government—is under threat. That perception has underpinned the widespread belief that Chinese growth won’t fall much below 7%, because that is the government’s desired target and Beijing is omnipotent.

Looming over all of this is China’s massive run-up in debt, which has increased by over $20 trillion—to around 300% of GDP—since the global financial crisis in 2008. All along, the bulls argued that Beijing has successfully managed every challenge to its three-decade economic boom, and that it could overcome the threat this debt represents. At a minimum, the argument went, China’s financial woes would be smaller than those of other countries with high levels of borrowing. This faith in Beijing encouraged many global hedge funds to pile into Chinese stocks.

But if Beijing can’t stop the market’s tumble, there could be a sudden shift in the perception of exactly how far economic growth might fall under the weight of too much debt. If that floor crumbles and the Chinese economy spirals downward, it will make the drama surrounding Greece feel like a sideshow. China has been the largest contributor to global growth this decade; Greece’s economy is about the size as that of Bangladesh or Vietnam.

There is no global drama that bears closer watching than Beijing’s battle for control.

Mr. Sharma is the head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management and the author of “Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles” ( Norton, 2012).

3a)

Why China's Stock Markets Matter

Analysis

- Beijing will continue to intervene where possible to prop up markets and market sentiment.

- A collapse of the stock market would likely increase deposits in ordinary bank accounts.

- This would compel Beijing to rely more heavily on banks to fuel growth and pressure China to accelerate financial liberalization efforts as a way to cultivate household consumption.

The Shanghai Composite Index fell 6 percent on July 3, rounding out a 28 percent decline since June 12, when the country's stock markets peaked. The deterioration occurred despite intensive government efforts to stabilize prices and revive investor sentiment. Overt attempts by Beijing included cutting benchmark interest rates and reserve requirement ratios and loosening restrictions on investor access to margin loans, in addition to less overt moves, such as direct interventions to prop up the market with government-backed purchases of blue chip stocks. On Friday, in a clear bid to win investor confidence in its oversight abilities, the securities regulator announced it would investigate signs of potential market manipulation. Yet so far, Beijing's efforts have failed to achieve the desired effect of stimulating, or at least stabilizing, China's leading stock markets.

In the days and weeks ahead, Beijing will not meekly accept the natural winding down of the past year's stock boom turned bubble. Rather, it will continue to work, both overtly and covertly, to prevent prices from collapsing outright — all while seeking to reshape investor sentiment and expectations through investigations, like those recently announced. The question of why Beijing feels compelled to take action remains, especially when any intervention risks exacerbating whatever financial and political fallout may come from an eventual market decline or crash. The answer to this question lies in understanding the role of stock markets in China's economy and Beijing's broader policy priorities, as well as evaluating the potential effects of a stock market crash on both.

Nurturing Consumer Growth

The Chinese government's core policy goal — the crux of its entire economic reform and rebalancing program — is to cultivate a domestic consumer base capable of supporting nationwide growth that is stable, sustainable and less exposed to fluctuations in external demand. To do this requires a boost in average incomes to a level where non-essential purchases become feasible for ordinary people. Additionally, China needs to instill in its citizens a sense of financial security adequate enough to convince them to spend — rather than save — their disposable income.

China has struggled on both fronts over the past two decades. Until recently, China was a country of near-universal poverty. Its post-1978 economic growth model, grounded as it was in low-cost exports and state-led investment into infrastructure construction, necessitated two policies: the systematic repression of manufacturing wages to maintain the competitiveness of exports and the suppression of interest rates on savings deposits. Keeping interest rates low ensured cheap financing for China's state-owned sector, which was responsible for the vast majority of infrastructure development and which survived on credit from state-controlled banks. These factors, more than any supposed cultural inclination to save, explain China's extraordinarily low levels of private household consumption relative to other parts of its economy — and compared to consumption levels in other countries.

For China's leaders, a key question over the past two decades has been how to cultivate greater household consumption without undermining the low-cost export and government investment-led economic growth model. Doing so required creating investment avenues by which ordinary Chinese citizens could achieve returns on their savings that outpaced inflation, but which did not direct those savings away from domestic export and construction industries. Allowing ordinary Chinese to invest their savings overseas was clearly not an option — not only would it direct those savings away from the domestic economy, but the free flow of capital in and out of China would constrain the government's ability to manage the yuan's value. Bearing this in mind, China's leaders in the early 1990s settled on two approaches: commercial real estate markets and stock markets. Both would give ordinary Chinese new opportunities to invest their savings and reap the rewards while simultaneously directing those savings into key industries and sectors, including housing and infrastructure construction and the state-owned sector, which enjoys disproportionately higher representation on China's largest stock exchange.

The Real Estate Boom

For most of the past 20 years, commercial real estate was by far the dominant avenue for ordinary Chinese to invest their savings, with stock markets playing a minor and unsteady second fiddle. Real estate and related industries formed the single largest component of China's economy. As long as home sales and prices rose, as they did with extraordinary consistency for two decades, real estate provided an unrivaled investment opportunity, one firmly backed by the Chinese government. This was especially true after the 2008-2009 global financial crisis decimated China's low-cost export sector, amplifying the importance of construction-related industries for employment and social and political stability. In comparison, China's stock markets, bedeviled by opacity and poor regulations, floundered. By 2009, most ordinary Chinese viewed investing in stocks as akin to playing the lottery.

To the extent that real estate was the primary means for ordinary citizens to increase their wealth, it also became critical to Beijing's efforts to stimulate domestic consumption. This in part explains the government's hesitancy to implement the kinds of policies that in the long run would contribute to cultivating domestic consumption. In the near term, however, bringing in policies such as deposit rate liberalization would raise costs for the state-owned companies largely responsible for real estate-related construction.

Yet now, after peaking, China's housing has entered a period of protracted decline. With real estate-related investments no longer promising the returns they once did, and with China's economy slowing, Beijing must find new tools for supporting domestic consumption. This is especially critical given that China is no longer able to rely on low-cost exports or the housing sector. Beijing must now look to private household consumption and consumption-driven industries as the primary drivers of national economic growth.

This is the backdrop against which the sharp, government-supported surge in China's stock markets over the past 12 months should be understood. It also helps explain why the government continues to support the stock market even as it becomes clear that the market is a bubble, and even as investor leverage rises, alongside the financial risks of a market collapse. In short, a collapse in the stock market, in a climate of stagnant-to-negative growth in real estate, would almost certainly lead to a drop in household consumption and thus in consumption-driven industries. This is exacerbated by an environment that lacks substantial alternative investment avenues, in a period of slowing economic growth, slowing wage increases and rising unemployment.

Private consumption is increasingly critical, not only to Beijing's long-term reform goals but also to maintaining economic growth, employment, and social and political stability in the near term. Beijing seeks to avoid, as long as it must, any actions that infringe on private consumption. If stock markets collapsed tomorrow, the most immediate effect — beyond widespread but containable ire over lost savings and a significant hit on business cash flows — would be a surge in state-backed bank deposits as ordinary investors move their capital to the only place offering safe, if modest, returns.

This is not necessarily a bad thing for Beijing. After all, China's state-controlled banking sector would be flush with capital and in a stronger position to pump credit into the economy as needed. At the same time, it would likely cut against the underlying thrust of China's reform and rebalancing program — specifically, the need to curb wasteful state-led investment, reduce the state-sector's reliance on artificially cheap financing and improve the ability of banks to price risk. All of this could ultimately combat the widespread capital misallocation that has characterized every prior instance of massive state-backed credit expansion in China. Over the past year, banks have become an increasingly important source of corporate financing. Amid a collapse in the stock market, a rapid surge of deposits into banks would force Beijing to turn once again to the financial sector to support the economy. In all likelihood, this would lead to a repeat of the same speculative bubbles that attended the post-2008 stimulus drive.

Alternatively, Beijing could try to compel banks to hang onto the surge in savings rather than expanding lending. This would realistically be done by raising deposit interest rates. Such a move would almost certainly trigger an economy-wide crisis as the state-owned sector, already suffering falling profits and hefty debt repayment costs, collapses. It would also be an enormous boon to ordinary Chinese citizens, who continue to park the vast majority of their funds in savings deposits. By forcing a broad restructuring of Chinese industry, this would substantially accelerate the central government's long-term reform plans. It remains doubtful that the Communist Party government could survive such a crisis intact. At any rate, it is highly improbable that Beijing would raise interest rates, a policy that stands a strong chance of undermining state security in the immediate term.

A Choice of Evils

This is the basic conundrum China's leaders face in determining whether and for how long to sustain the current stock market boom. Barring a radical lifting of restrictions on overseas investment or a sharp increase in deposit rates, China effectively lacks channels for ordinary citizens to generate wealth beyond investment in real estate and stocks. Real estate is slowing, weighed down by years of accumulated oversupply. It no longer promises the returns it once did. If stocks decline, it is unclear what else ordinary people can rely upon to generate returns. The impact of a stock market decline on private consumption growth would only compound its effects on corporate balance sheets and investment, and thus on employment and economic growth.

The bottom line is that Beijing has an underlying interest in ensuring that China's stock markets do not collapse. Therefore, the government will likely continue to intervene to the best of its ability, propping up markets and market sentiment whenever the risk of a major sell-off becomes too great. This does not mean that stock prices won't slide further, or that the market will stabilize — indeed, it could well become even more volatile over the coming months. But it does reinforce the fact that until Beijing invents more avenues for investment, or unless it embraces interest rate hikes and any post-crisis restructuring, it will have to rely on the few tools available to ensure that citizens can generate the wealth and financial security they need to consume. Beijing's reform goals, as well as the ability to manage China's slowdown, depend on this.

4)

Book Review | Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide

by

Michael B. Oren, Random House, 2015, pp.432.

Michael B. Oren, Random House, 2015, pp.432.David E. Lowe is the Vice President for Government Relations and Public Affairs at the National Endowment for Democracy. The views expressed here are solely his own.

During the 2008 US Presidential campaign, the historian Michael Oren accepted an assignment from a security affairs journal to research and write about candidate Barack Obama’s views on Middle East issues, including those related to Israel. ‘My findings,’ he writes in his recently published memoir of his four years as that country’s US Ambassador, ‘helped ensure that the future president would rarely surprise me.’

Fulfilling a lifetime dream, in 2009 Oren took on the assignment of representing his adopted country in the country where he was raised and educated. He tells his very personal story in Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide.

Oren’s memoir was released in late June to a chorus of criticism that followed a series of slightly provocative opinion pieces by the author to promote the book. The controversy they stimulated is both misleading and unfortunate; misleading because the book itself is written in an analytical, not to mention diplomatic voice; and unfortunate because, far from seeking controversy, it makes an honest effort to report on, and make sense of, the developments, including misperceptions and mutual suspicions, that have strained the US-Israeli relationship over the past six years.

The most vociferous reaction has come from the Obama administration, clearly unhappy with Oren’s take on the points of friction that emerged between two longtime allies over issues ranging from the peace process with the Palestinians and the Gaza blockade to the nuclear negotiations with Iran. But in each case, Oren is careful not to paint with too broad a stroke his criticism of the US President. Indeed, he takes great pains to refute the argument, often voiced by Obama’s detractors in Congress and conservative media, that he is ‘anti-Israel.’

In Oren’s estimation, the president ‘cared for Israel certainly as much as he cared about most other foreign countries and understood the deep affection for Israel felt by … the large majority of Americans.’ On the other hand, the Israel the president admired was ‘an idealized Israel – not the Israel of the settlers and their right-wing backers, a state that was part of the solution, not the problem.’

And just what was the problem? As outlined in his 4 June 2009 speech to a group of Middle Eastern students in Cairo, it was a troubled US relationship with the Muslim world that the president was determined to fix. He was convinced that the best way to achieve the desired goal of improving that relationship was to solve the Israel-Palestinian conflict. It was this concept of ‘linkage’ that the President’s national security advisor emphasised in an address early in the administration to J Street, a relatively new American organisation known primarily for its strident criticism of Israeli government policies.

With the election of a Likud government led by Benjamin Netanyahu shortly after the first Obama inauguration, the stage was set for a series of policy conflicts between two increasingly distrustful allies that were to make Oren’s tenure in Washington so challenging, including: the administration’s insistence on a ‘settlement freeze,’ broadly defined to include Jerusalem neighbourhoods, prior to negotiations with the Palestinians on the future of the West Bank; the US demand for a Netanyahu apology to Turkey’s President Erdogan following the Mavi Marmara incident in which Israelis attempting to enforce a legal blockade against ships making deliveries to Hamas-controlled Gaza were met by a carefully planned attack by members of a Turkish extremist group and defended themselves, resulting in a number of deaths; the president’s call for a return to Israel’s 1967 borders, which drew a strong response from the prime minister in a face-to-face meeting between the two that infuriated Obama and his advisors.

Looming above all of these conflicts were the tensions arising over the Iranian nuclear threat, tensions exacerbated by the administration’s secret negotiations that kept the Israelis in the dark. While resisting the efforts of Congress to expand sanctions against Iran, the president and his advisors made known their strong disapproval of any attempt by Israel to attack its nuclear facilities. For its part, the Netanyahu government was – and continues to be – convinced that the US negotiation over Iran’s nuclear program is headed down the same path as the unsuccessful one it conducted with North Korea two decades ago.

Ally reinforces the conventional wisdom that US presidents, hamstrung by the American constitutional system of checks and balances on domestic issues, are preeminent in the shaping of foreign policy. In contrast with the image of a leader who is often seen as indecisive in dealing with autocrats challenging American national security interests, Oren portrays the president’s approach to dealing with Israel’s leaders as firm and determined.

Although Oren’s overarching observations of his period as the Israeli Ambassador to the US are sound, he does make the occasional misstep. One of them involves his application of amateur psychology to those he is trying to understand, the source of some of the criticism of his pre-publication opinion pieces. While he can be excused for a two sentence speculation about the impact of growing up in a broken family on Obama’s world view, his musings on the harsh criticism directed at Israel by American Jewish journalists is more problematic. That criticism he attributes to their ‘insecurity’ as Americans, even their ‘fear of anti-Semitism.’ The reality is far simpler: a combination of ideology and partisanship, along with disappointment with an Israel whose democratic electorate selects leaders they dislike.

The author’s disapproval of the administration’s handling of the misnamed Arab Spring is useful in highlighting the differences between the perceptions of Israelis and Americans on the prospects for democracy in the region. But while the latter can be faulted for their overly optimistic initial assessment of what would follow in Egypt after the 2011 events in Tahrir Square, Oren’s harsh criticism of the US administration for not standing with Mubarak overstates its role in his downfall.

Oren’s story concludes with his election to the Knesset in March 2015. His experience as ambassador served to reinforce his conviction of the mutual advantages Israel and the US derive from their long term relationship. ‘One immense distinction,’ he contends, ‘separates contemporary Israel from that of the eve of the 1967 and 1948 wars: Israel is no longer alone.’ For their part, Americans cannot detach from the Middle East, ‘for it will follow them home. A robust Israel helps to keep that Middle East at bay and assists in safeguarding that home.’ One can only hope that those who were so quick to criticise the author will find a way to absorb this central message.

4a)

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5)"Hello Dick: As you know, I am not a Jew. But I believe that, as so often in the past, attitudes towards Jews are proving to be telling and deeply worrisome indicators of the moral and intellectual health of society. So the current drift of policymaker and intellectual opinion towards Israel is very troubling in itself, but it is also a signal of a deeper malaise. (The intellectuals—most of whom are astoundingly unintelligent--are again proving that they are, by far, the most dangerous class.) I can only speak for myself, but I will never support any politician who gives me the slightest reason to doubt his or her firm and principled commitment to Israel’s security. However, I fear that all that may be beside the point because in a few years, given our deep structural fiscal imbalances and our eroding morale, the United States is going to lack both the capacity and the will to be of much help to Israel." S--

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5)"Hello Dick: As you know, I am not a Jew. But I believe that, as so often in the past, attitudes towards Jews are proving to be telling and deeply worrisome indicators of the moral and intellectual health of society. So the current drift of policymaker and intellectual opinion towards Israel is very troubling in itself, but it is also a signal of a deeper malaise. (The intellectuals—most of whom are astoundingly unintelligent--are again proving that they are, by far, the most dangerous class.) I can only speak for myself, but I will never support any politician who gives me the slightest reason to doubt his or her firm and principled commitment to Israel’s security. However, I fear that all that may be beside the point because in a few years, given our deep structural fiscal imbalances and our eroding morale, the United States is going to lack both the capacity and the will to be of much help to Israel." S--

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment