---

Obama's nose is under the tent? While signing people up for 'Obamascare' why not help them register to vote for more boondoggles brought to our nation by the Progressives!(See 2 below.)

---

Flawed assumptions: " Rather than face the ugly truth about the contemporary face of fascism, western politicians have manufactured an elaborate set of political illusions, a kind of strategic transference, if you will. The most pernicious illusion is the "two-state" solution. "(See 3 below.)

---

Mona Charen reviews Sowell's New book: "Intellectuals and Race." (See 4 below.)

---

Efrig is bullish and Curzio believes he has found some bargains (See 5 and 5a below.)

---

Tongue in cheek article by friend of our son who wrote: "This the daughter of a very dear friend. she works in the pizza shop at the end of our street. Brilliant." (See 6 below.)

---

Mort Zuckerman continues having doubts. To restore our nation's vitaiity we need hard headed reasoning and solutions. (See 7 below.)

---

Dick

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1)Bullard: Fed to Move ‘Full Steam Ahead’ With Bond Purchases

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard said the Fed is in no hurry to reduce its record bond buying with inflation running below its 2 percent target.

“It is full steam ahead right now,” Bullard said on Bloomberg Radio’s “Hays Advantage” with Kathleen Hays. “That is exactly what the committee is doing.”

A voter on monetary policy this year, Bullard was one of the first Federal Open Market Committee officials to urge slowing the pace of bond purchases in 2013 if warranted by economic reports, a position taken by Chairman Ben S. Bernanke last month. In 2010 Bullard initiated calls for a second round of bond buying, which ran from November 2010 until June 2011.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note fell Thursday to a two-month low, showing there’s little concern among investors about inflation risk. The note yielded 1.81 percent at 3:13 p.m. in New York, down from 1.86 percent Thursday.

Consumer prices rose just 1.3 percent in February from a year earlier, according to an inflation gauge favored by the Fed, and growth has been too weak to generate jobs for millions of fired workers. Unemployment in February was 7.7 percent.

Monetary policy is currently “appropriate,” Bullard said in the interview, adding that he didn’t call for a reduction in asset purchases at the FOMC’s meeting in March.

‘More Comfort’

“I don’t think we have to be in any hurry” to cut stimulus, Bullard said. “The committee has more comfort in a situation in which inflation is low.”

The FOMC has leeway to review economic data in the next few months and determine whether to pare back asset purchases known as quantitative easing, Bullard said.

“We are not forced into a decision right now,” he said. “If we continue to get good data on the economy, then we will have a decision to make.”

The economy is likely to grow around 3 percent this year, Bullard said. “Things are pretty good right now for the U.S. economy,” he said. “The surprise has been to the upside.”

Recent economic data has shown a pickup in growth and an improvement in the labor market. About 195,000 jobs were added last month and the unemployment rate stayed at 7.7 percent, according to the median estimates of economists surveyed by Bloomberg ahead of an April 5 report.

Less Worried

Bullard said he is less worried than some private forecasters about a “spring swoon,” or a mid-year slowdown that has occurred during the past two years. Risks from the European debt crisis have waned during the past two years, so global conditions probably won’t impair growth, he said. Also, fiscal tightening may crimp consumer spending less than many economists estimate.

The St. Louis Fed chief said when it comes time to slow purchases, he favors reducing the pace by small increments in response to changes in the economy.

“I would be very comfortable moving in small amounts — $10-or-$15 billion at a time,” Bullard said in the interview at the St. Louis Fed. “We are getting much closer” to the committee agreeing to a tapering approach, as indicated by Bernanke’s comments last month.

Small changes in bond buying probably won’t disrupt stock or bond markets, Bullard said. In contrast, a sudden halt in the buying could jolt investors, he said.

Compared to other policy makers, Bullard is viewed by investors as unusually influential, according to Macroeconomic Advisers LLC. His speeches and interviews prompted a bigger increase in bond yields than any other Fed official last year, according to a March 8 report by the Washington-based firm.

Exceeded Expectations

Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo said that while some economic data have exceeded expectations, he would like to see more consistent job growth before he can support curbing the central bank’s $85 billion monthly pace of bond buying.

“At the very least, what I’d like to see is some good healthy peaks that have job creation well above the rate of new entrants into the labor market, followed not by valleys that take back some of that progress but at the very least by a nice plateau that can be the basis for some more peaks later,” Tarullo said in a CNBC interview.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2)Tens of thousands Obamacare 'navigators' to be hired

By Paul Bedard

Tens of thousands of health care professionals, union workers and community activists hired as "navigators" to help Americans choose Obamacare options starting Oct. 1 could earn $20 an hour or more, according to new regulations issued Wednesday.

The 63-page rule covering navigators, drawn up by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, also said the government will provide free translators for those not fluent in English -- no matter what their native language is."The proposed requirements would also include that such entities and individuals provide consumers with information and assistance in the consumer's preferred The rules also addressed conflict of interest and other potential issues that navigators could face as the public's first stop on the Obamacare trail.

It is still not clear how many navigators will be required. California, however, provides a hint. It wants 21,000.

That could be an expensive proposition. The proposed rules, now open for public comment, suggest an estimated pay of $20-$48 an hour.

"There is a section of the proposed regulation where our financial analysts estimate how financially significant the regulation will be. In that section, for the purposes of estimating that impact, they assumed navigators would be paid an average of $20 an hour. That is an estimate, not a recommendation or a requirement," said an administration official. "States and organizations are not required by the federal government to set any payment levels for these employees," he added.

The rules allow navigators to come from the ranks of unions, health providers and community action groups such as ACORN and Planned Parenthood. They are required to provide unbiased advice.

Some in Congress are already wary of the navigators. Louisiana Republican Rep. Charles Boustany Jr., chairman of the House Ways and Means Oversight subcommittee, has raised questions about a voter registration provision in the Obamacare application Americans will have to fill out to receive health care, and whether Democratic-leaning activists will influence which party people choose to join.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3)More is Never Enough

By G. Murphy Donovan

Barack Hussein Obama finally went to Israel. Before the trip, America had a schizophrenic, yet constant, Mideast foreign policy; stroking autocratic Arabs and alienating democratic Israelis.

And now the rolling Sunni revolution in Arabia is converging on Mecca and Medina from two directions. And when Bashir Assad falls, the oil oligarchs will feel the heat from two sides. Shia theocrats and Sunni Islamists have the same target set. The Arab establishment is ground zero.

And now the rolling Sunni revolution in Arabia is converging on Mecca and Medina from two directions. And when Bashir Assad falls, the oil oligarchs will feel the heat from two sides. Shia theocrats and Sunni Islamists have the same target set. The Arab establishment is ground zero.

3)More is Never Enough

By G. Murphy Donovan

Barack Hussein Obama finally went to Israel. Before the trip, America had a schizophrenic, yet constant, Mideast foreign policy; stroking autocratic Arabs and alienating democratic Israelis.

Indeed, the 'Brennan' doctrine took sides in the Shia/Sunni nuclear competition, the Ummah Armageddon that haunts every Semitic nightmare. American solidarity with Arabs, especially Saudi Arabia and the emirates, has become a peculiar variety of national masochism.

Most Islamist terror originates with Sunnis. Irredentist Sunni theology originates in Egypt and Saudi Arabia and finds funding and sectarian solidarity in the Emirates, putative allies all.

And recall the first Islam bomb, a Sunni gift from another dubious 'ally,' Pakistan. The Sunni nuclear threshold was breached 20 years ago while American intelligence slept. This is the same Pakistan that harbored Osama bin Laden for ten years after 9/11. This is the same Pakistan which is always just a bullet away from dictatorship or theocracy.

Ten years of South Asia weapons testing in the 1980s hardly made a strategic ripple. Turning a blind eye to nuclear weapons in Pakistan is a little like ignoring a straight razor on a crowded playground.

And now the rolling Sunni revolution in Arabia is converging on Mecca and Medina from two directions. And when Bashir Assad falls, the oil oligarchs will feel the heat from two sides. Shia theocrats and Sunni Islamists have the same target set. The Arab establishment is ground zero.

And now the rolling Sunni revolution in Arabia is converging on Mecca and Medina from two directions. And when Bashir Assad falls, the oil oligarchs will feel the heat from two sides. Shia theocrats and Sunni Islamists have the same target set. The Arab establishment is ground zero.

The ayatollahs of Tehran are buying time to build another bomb too. John Kerry, former anti-war zealot,

Ensign of Islamic Resistance

is touring the Levant; threatening to intervene in Syria on behalf of Sunni Islamists -- another U.S. secretary of state choosing winners and losers in the great minus-sum game. America learned nothing from Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Tunisia, Tahrir Square, and Benghazi.

The nuclear dimension of Islamic politics is unique in the annals of death wishes; a fascination with improved ways to kill coupled with suicide theology and cultural decay. Child marriage and martyrdom flourish side by side at the expense of education and social maturity. Beyond symptoms, the core pathology, the modern incarnation of fascism, is dressed in a burkha of religion -- a perennial toxin in Muslim culture.

Why would any rational Western democracy -- apostates or infidels --continue to throw dogs into this fight?

No matter. Americans and Europeans press on into the dark night of tribal feuds and religious quarrels. The ancient wars between modernity and irredentism metastasize today under a variety of labels; revolution, regime change, civil war, insurgency, and terrorism just to name a few.

Rather than face the ugly truth about the contemporary face of fascism, western politicians have manufactured an elaborate set of political illusions, a kind of strategic transference, if you will. The most pernicious illusion is the "two-state" solution.

The binary formula, an Israel beside a Palestine, is underwritten by several flawed assumptions, not the least of which is poor arithmetic. There is no single representative of Palestinian interests. Israel's proximate enemies are three in number, Hezb'allah, Hamas, and Fatah. Only Fatah pretends to make a deal.

And the four Arab nation states bordering Israel have probably killed more Palestinians than the IDF. Palestinian militias have been purged from Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt. Yasser Arafat was run out of Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia before Israeli indulgence allowed his return to the West Bank. The terror vacuum in Lebanon was filled by Hezb'allah. Alas, all of those Arab states bordering Israel are capable of influencing Palestinian politics when it suits their needs.

Yet, who believes that a sovereign Palestine will be a good or pacific neighbor? Who believes that the UN, or the Arab League for that matter, needs another dysfunctional member?

Even if Israel could negotiate a settlement with non-state players, any agreement would have to be underwritten by four unstable, if not belligerent, Arab states. The likelihood of Israel accommodating one Muslim partner is slim; the probability of pleasing seven is near zero.

The Palestine dilemma has always been an Arab problem, but Arab governments have always preferred to let the refugees from lost Arab wars stew on the Israeli frontier in a pyrrhic quest for sovereignty. Implicitly, that which could not be done by conventional force of arms, might be done by time, terror -- and a poison pill like Palestine.

In sixty years, Israel has made numerous one-sided financial, humanitarian, and territorial concessions. Little of this is reciprocated at the borders where Arab state players, at worst, sponsor and, at best, ignore terror cells. Israel's borders might be secured in a fortnight were it not for indifferent or duplicitous Arab neighbors.

Muslims within Israel live better than any minority in the Arab world, an Islamic world where Jews have been systematically purged. Twenty percent of Israelis are Arabs, living peaceably in Israel. The third holiest mosque of Islam survives in Jerusalem. How many synagogues stand in Mecca, Medina, or the emirates? If Jews need to give more for peace; how much is enough?

The two-state formula isn't a solution, it's a symptom; a sign of moral cowardice and political charades. Israel is not likely to make a suicide pact with hostile neighbors and the Arab world is unlikely to give up the Palestinian cause; its favorite crutch, its favored excuse, and its favorite wedge issue.

And western political elites, right and left, can't stop doing what doesn't work either; endorsing a "two-state" chimera for example. Intemperate indulgence of Muslim rage prevails in America, Europe, and even parts of Israel. Social democracies, and their embedded dependencies, are the captives of fear -- and excess. More of the same is always better. Clear-eyed candor is seldom an option. Unfortunately, more is never enough when the threat is fascism underwritten by religious imperialism.

The author writes frequently about national security, military affairs, and Intelligence.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4)Sowell Does It Again

I plunged into Thomas Sowell's latest book "Intellectuals and Race" immediately upon its arrival but soon realized that I needed to slow down. Many writers express a few ideas with a great cataract of words. Sowell is the opposite. Every sentence contains at least one insight or fascinating statistic, frequently more than one. His newest offering is only 139 pages (excluding notes), but tackles a huge question -- the damage that bad ideas on matters of race peddled by self-satisfied intellectuals have had and continue to have on the world.

Race is almost a national psychosis for Americans, distorting our perceptions and inhibiting rational debate. Sowell places our obsession in context both historically and internationally.

Progressive (i.e. early 20th century) intellectuals, some with the very best pedigrees, espoused views on race that make our skin crawl today. Madison Grant, influenced by the popularity of eugenics among intellectuals, published "The Passing of the Great Race," a warning that "superior" races (whites and particularly "Nordics") were losing ground to the "lower races." A believer in "genetic determinism," he disdained immigration as the "sweepings" from European "jails and asylums" and worried that "the man of the old stock is being crowded out ... by these foreigners just as he is today being literally driven off the streets of New York City by the swarms of Polish Jews."

His book was recommended by the Saturday Evening Post and reviewed in Science. It was translated into French, Norwegian and German. Hitler called it his "Bible."

There's nothing easier than to condemn such ignorance and bigotry today -- though few note, as Sowell (and Jonah Goldberg) do, that liberals/progressives, including Richard T. Ely, Edward A. Ross and Francis A. Walker, were among it chief propagators.

More challenging is to recognize the follies of your own time and to examine critically the assumptions that underlie our current racial theories. As he has in some of his other work (for example, in the absorbing "Ethnic America"), Sowell challenges what he calls the "moral melodrama" -- the belief that observed differences in outcomes for racial and ethnic groups are the result of discrimination. This unsupported assumption underlies our whole scheme of "disparate impact" and "affirmative action" programs.

Ethnic groups have different histories, cultures, traditions, median ages and abilities. Geography, disease, conquest and other factors affect the way cultures and peoples develop. Into our own time, economic disparities between the peoples of Eastern Europe and Western Europe were more pronounced than those between American blacks and whites. During the First World War, black Army recruits from Ohio, Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania scored higher on mental tests than whites from Georgia, Arkansas, Kentucky and Mississippi.

People of Japanese ancestry produced 90 percent of the tomatoes and 66 percent of the potatoes sold in Brazil's Sao Paulo province in 1908. "In 1948, members of the Indian minority owned roughly nine-tenths of all the cotton gins in Uganda. In colonial Ceylon, the textile, retailing, wholesaling, and import businesses were all largely" in Indian hands "rather than in the hands of the Sinhalese majority."

Sowell is particularly fond of quoting the economic statistics documenting minority groups who outperform the majorities in many nations. It includes the Italians in Argentina, the Chinese in Malaysia, the Lebanese in Sierra Leone, Greeks and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and, he might easily have added, Asians in the U.S. today. The urge to attribute all disparities to discrimination, Sowell argues, a) doesn't withstand scrutiny -- black unemployment, for example, was lower than white in 1930 when there was far more anti-black discrimination than today; and b) encourages damaging and divisive "solutions" like affirmative action that harm both the intended beneficiaries and deserving members of the majority group, and encourages sometimes violent conflict as in Sri Lanka, Canada, Hungary, Nigeria and many other nations.

In his survey of damaging thinking about race, Sowell makes extended stops at IQ, multiculturalism, crime and other matters. He brings to every subject the depth of understanding, copious research and impatience with cant that have made him one of America's most trenchant thinkers

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5).

| |||||||

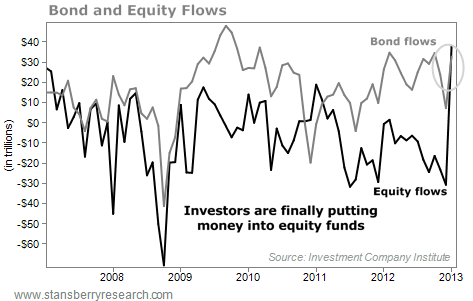

| Last week, I showed you a handful of charts that dispel a common misconception… one that is keeping thousands of retirees up at night. I dispelled the idea that the U.S. economy is running off the rails… that we are in a recession, or worse, a depression. Despite the facts I showed you… and despite the fact that stocks are still a good value (read more here), the stock market still hasn't boomed like I believe it will. But that's about to change. Here's why… Investors spent much of 2012 "stampeding" into bond funds. Bonds are seen as "super safe" investment vehicles… much safer than stocks. A stampede into bonds is a classic sign that people are scared of a volatile and uncertain stock market. And even with interest rates near all-time lows, people were still moving gobs of money into bonds and bond funds. As the chart below shows, they're still putting money into bond funds… but they're finally starting to put money back into stocks as well. This chart displays the amount of money flowing into bond funds (the gray line) and the amount of money flowing into stock funds (the black line). As you can see on the right side of the chart, the money flow into stocks just spiked higher… It's now equal to the money flowing into bonds.  This spike higher in equity flows tells us that "Mom and Pop" investors are finally getting interested in stocks again. Yes, stocks have enjoyed big returns in the past few years… but it usually takes several years of great performance to draw in the public after it has been burned like it was in 2008. The charts in last week's essay show that the economy is growing slowly. And despite what some folks tell you, inflation is still not a major concern right now. This is a good environment for stocks and – under normal times – bonds. But after the "stampede" into bonds, I think the risk here is too high. Plus, the dividend yields on stable (and even growing) blue-chip companies like Automatic Data Processing, Wal-Mart, and Wells Fargo make stocks a better choice for your portfolio in 2013. We've had low interest rates, muted inflation, and relatively cheap stock market valuations for a while. And no surprise, the market has responded by approaching all-time highs. Now, shifting investor sentiment could kick the rally into a higher gear. The recent spike in money flow is a clue that this is happening. That's why it's best to stay long stocks right now. They've had a great first quarter (up 10%)… but they're going to go up even more in 2013. Here's to our health, wealth, and a great retirement, Dr. David Eifrig 5a)

6)I To (All) the Colleges That Rejected Me If only I had a tiger mom or started a fake charity.By SUZY LEE WEISS

Like me, millions of high-school seniors with sour grapes are asking themselves this week how they failed to get into the colleges of their dreams. It's simple: For years, they—we—were lied to.

Colleges tell you, "Just be yourself." That is great advice, as long as yourself has nine extracurriculars, six leadership positions, three varsity sports, killer SAT scores and two moms. Then by all means, be yourself! If you work at a local pizza shop and are the slowest person on the cross-country team, consider taking your business elsewhere.

What could I have done differently over the past years?

For starters, had I known two years ago what I know now, I would have gladly worn a headdress to school. Show me to any closet, and I would've happily come out of it. "Diversity!" I offer about as much diversity as a saltine cracker. If it were up to me, I would've been any of the diversities: Navajo, Pacific Islander, anything. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, I salute you and your 1/32 Cherokee heritage

I also probably should have started a fake charity. Providing veterinary services for homeless people's pets. Collecting donations for the underprivileged chimpanzees of the Congo. Raising awareness for Chapped-Lips-in-the-Winter Syndrome. Fun-runs, dance-a-thons, bake sales—as long as you're using someone else's misfortunes to try to propel yourself into the Ivy League, you're golden.

Having a tiger mom helps, too. As the youngest of four daughters, I noticed long ago that my parents gave up on parenting me. It has been great in certain ways: Instead of "Be home by 11," it's "Don't wake us up when you come through the door, we're trying to sleep." But my parents also left me with a dearth of hobbies that make admissions committees salivate. I've never sat down at a piano, never plucked a violin. Karate lasted about a week and the swim team didn't last past the first lap. Why couldn't Amy Chua have adopted me as one of her cubs?

Then there was summer camp. I should've done what I knew was best—go to Africa, scoop up some suffering child, take a few pictures, and write my essays about how spending that afternoon with Kinto changed my life. Because everyone knows that if you don't have anything difficult going on in your own life, you should just hop on a plane so you're able to talk about what other people have to deal with.

Or at least hop to an internship. Get a precocious-sounding title to put on your resume. "Assistant Director of Mail Services." "Chairwoman of Coffee Logistics." I could have been a gopher in the office of someone I was related to. Work experience!

To those kids who by age 14 got their doctorate, cured a disease, or discovered a guilt-free brownie recipe: My parents make me watch your "60 Minutes" segments, and they've clipped your newspaper articles for me to read before bed. You make us mere mortals look bad. (Also, I am desperately jealous and willing to pay a lot to learn your secrets.)

To those claiming that I am bitter—you bet I am! An underachieving selfish teenager making excuses for her own failures? That too! To those of you disgusted by this, shocked that I take for granted the wonderful gifts I have been afforded, I sayshhhh—"The Real Housewives" is on.

Ms. Weiss is a senior at Taylor Allderdice High School in Pittsburgh.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

7)The Grand Illusion

The Obama administration is more inclined topublic relations than hard-headed pragmatism in dealing with unemployment

Which way are we going? The stock market has revived, though it still is off a high in real terms. There's suddenly good news about housing demand, which is showing signs of life after six years of stagnation. Yet Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke warns that the package of fiscal cutbacks – the fiscal cliff, sequester, and other cuts – is set to reduce growth by 1.5 percentage points. He calls that "very significant" and adds that "job creation is slower than it would be otherwise." This is the key to where we are. New research from the Brookings Institution concludes that rising inequality in the United States is not something that will vanish with a real recovery. It is here to stay, a reflection of an increasingly calcified society and a whole crisis in itself.

The present phase of our Great Recession might be called the Grand Illusion, because all the happy talk and statistics that go with it, especially on the key indicator of jobs, give a rosier picture than the facts justify. We are not really advancing. We are, by comparison with earlier recessions, going backward. We have a $1.3 trillion budget deficit. And despite the most stimulative fiscal policy in our history and the most stimulative monetary policy, with a trillion-dollar expansion to our money supply, our economy over the last three years has been

declining or stagnant. From growth in annual GDP of 2.4 percent 2010, we bumped down to only 1.8 percent in 2011 and were still down at 2.2 percent in 2012. The cumulative growth for the last 12 quarters was just 6.2 percent, less than half the 15.2 percent average after previous recessions over a similar period of time. It is the slowest growth rate of all the 11 post-World War II recessions.

What has gone wrong? There seems to be a weakness in the investment of private capital. Today, corporate spending on investments is the weakest it has been in six decades. The billions invested in the Internet, spreading its application and comingling the technology with labor, boosted multifactor productivity but, as David Rosenberg of wealth-management firm Gluskin Sheff points out, most of that occurred several years ago. As he has written, a capex-led business recovery that breeds sustained productivity growth and decent job creation is what underscores the best and longest economic expansions since the end of WWII.

Anemic growth looks likely to continue because of various downers implicit in Bernanke's caution. Sequestration will take $600 billion of government expenditures out of the economy over the next 10 years. Payroll taxes up 2 percent hit about 160 million workers and will drain $110 billion in aggregate demand. The Obama health care tax will be a $30 billion-plus drag. The surge in gasoline prices by some 50 cents recently may be temporary, as Bernanke suggests, but meanwhile represents another $65 billion of consumer cash flow. Conservatively, these nasties add up to roughly a 2 percent hit to baseline GDP growth when we are barely able to muster 2 percent growth.

Then there's housing. Yes, it is nice to see a surge in some areas. But millions of homes are owned by banks or are in the foreclosure process. The New York Times noted last week that

the home where Bernanke was raised, in a small town in South Carolina whose unemployment rate was recently 15 percent, had just been foreclosed upon the last time he visited, and one of his relatives was unemployed. Talk about symbolism. Single-family home sales and starts are barely off their depressed levels, and have only recouped 17 percent of recession losses. The housing market is mostly driven by investor-based, rental-related, multifamily buying activity, reflected in the fact that multiple housing units have reversed more than 70 percent of the damage they sustained from the recession.

Our economy's most important player, the consumer, offers no relief from this cascade of downers. About 70 percent of national expenditures come from consumers, but their confidence level has dropped to only 58.6 percent. Restaurant traffic, one of the most reliable trend indicators, has slipped to a three-year low. In fact, the only reason that real consumer spending is not shown as contracting is because personal savings rates since November 2007 have declined from 6.4 percent to around 2.5 percent of incomes.

Still, can't we take comfort in headlines celebrating the decline in unemployment to 7.7 percent? Not really. If you add in all the unique categories of people not included in that number, such as "discouraged workers" no longer looking for

a job, involuntary part-time workers, and others who are "marginally attached" to the labor force, the real unemployment rate is somewhere between 14 and 15 percent. No wonder it has been harder to find word during this recession than in previous downturns.

Though last month we theoretically added 236,000 jobs, these numbers are misleading, too, because so many of the jobs are in the part-time, low-wage category. So the backdrop to the most recent job numbers is the fact that multiple job-holders are up by 340,000 to 7.26 million. In essence then, all of the "new" positions are going to people who already are working,

mostly part time. It is clearly more important to create jobs for people who aren't. Other aspects of the jobs picture deteriorated, too. The pool of people unemployed for six months or longer went up by 89,000 to a total of 4.8 million, and the average duration of unemployment rose to 36.9 weeks, up from 35.3 weeks.

Moreover, the decline in the unemployment rate to 7.7 percent is shaky. It reflects the departure from the workforce of some 130,000 individuals. A change in the denominator makes the unemployment numbers look better than they are. The labor force participation rate, which measures the number of people in the workforce, also dropped to around 63.5 percent, the lowest in more than 30 years. The workweek remains short at 34.5 hours. Quite simply, employers are shortening the workweek or asking employees to take unpaid leave in unprecedented numbers, and these people are not included in the unemployment numbers.

Clearly, the rate of job recovery has slowed drastically. Typically it takes 25 months to reach a new post-recession peak in employment, but today we are over 60 months away from that previous high, and we are still down 3.2 million jobs. We need between 1.8 million and 3

million new jobs every year just to absorb the labor force's new entrants. At the current rate, we will have to wait seven years to restore the jobs lost in the Great Recession, and we will need 300,000 or more hires every month to recover substantially above the current levels. The prospects for that are gloomy, since employers now feel they can do with fewer workers. Over 20 percent of companies say that employment in their firms will not return to pre-recession levels.

In the face of these figures, the government is just whistling in the dark. The programs it has announced are sensible, but don't do anywhere near enough to plug the gap in workers needed with skills in science, technology, engineering and mathematics – the best way to deal with

the threat of a big permanent underclass. Nor is there any sense of a vigorous follow-through on multiple well-intentioned programs. We are told we live in an accelerated world, and so we do in communications. But when will we see reform of a patent system that imposes long delays on innovators and inventors and entrepreneurs seeking approvals? It often takes two years to obtain the environmental health and safety permits to build a modern electronic plant, a lifetime in the tech world.

A dramatic consequence of the inertia is that our trade in high-tech products has gone from a $29 billion surplus to a $60 billion-plus deficit.

When employers can't expand or develop new lines because of the shortage of certain skills,

the employment opportunities for the less skilled are restricted. Government must restore and multiply funds for training programs, especially vocational training and postsecondary education. And it must support every program to strengthen science, technology, engineering and math in high schools and at the university level, as well as broadening access to computer science. Until we get such programs properly underway, we should increase the number of annual visas for foreigners skilled in science and technology. They are not job destroyers, as nativist sentiment suggests. They are job creators, and not only that. They are job multipliers. Barring their entry or residence means they will compete against us in the industries that are both growing and competitive. It is astounding that we attract the brightest and the best brains to our universities, the world's best, and then send them packing. We must re-conceptualize immigration as a recruiting tool and open the door to the skilled and the educated. It is disappointing that so soon in a new administration, decisively elected, both party leaderships seem still stuck in a campaigning mode. It isn't just that agricultural companies lack the labor to pick crops of citrus fruits and onions, but that we are stupidly cutting off one of the great sources of innovation. About half the companies in the Fortune 500 owe their origins to the ideas and enterprise of immigrants. Diversity breeds ideas. Look at the history of America.

What we get from the administration instead of pragmatism is politics; instead of constructive strategies shed of ideology, we get steady attacks demonizing the wealth creators and discrediting the private sector, along with rhetoric that seeks to exploit divisions by blaming

the rich and positioning them against the rest, as if government is not part of the problem.

No wonder Fox News found earlier this year that 48 percent of us believe America is weaker than it was five years ago, while just 24 percent think the nation is stronger. Have we really so lost our mojo? Have we lost our way? As 18th-century economist and writer Adam Smith once observed, "there is a great deal of ruin in a nation." Indeed there is. One serious recession

does not mean the beginning of the end of a great power. But the risks will multiply so long as we remain locked in a rancorous political culture, and have a leadership more inclined to public relations than hard-headed pragmatic recognition of what must be done to restore America's classic vitality.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

No comments:

Post a Comment